- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

Fashioning Identity

Native tradition meets artistic innovation in the mola textiles of Guna women

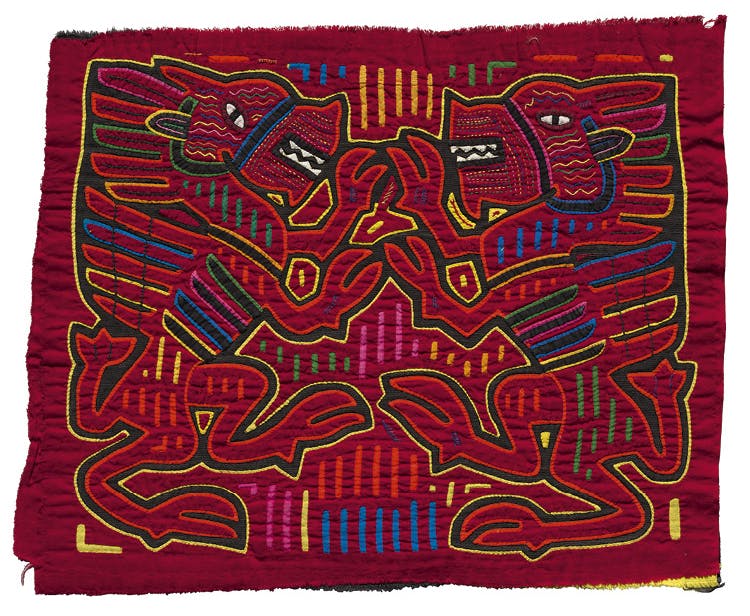

Rampant Lions Mola Panel c. 1950–70. Republic of Panamá, Gunayala Comarca, Guna people, Gardi Coiba community. Cotton; reverse appliqué, appliqué, embroidery; 37.5 x 46 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. F. Louis Hoover, 1971.197l

The indigenous Guna live on sovereign territory, the Gunayala Comarca (Gunaland Province), in the Republic of Panamá. Guna women spend hours every day hand sewing intricate designs into fabric panels destined to form the fronts and backs of blouses known as molas, a principal element of traditional dress. Vibrant, eye-catching, and uniquely Guna, molas have become the single most recognizable element of Guna cultural identity.

Fashioning Identity: Mola Textiles of Panamá marks the debut of the art of the mola at the museum and celebrates several gifts that have entered the collection over the years. Among them is a 1971 donation of 30 mola panels by Dr. Louis Hoover, an art professor in Illinois, and his wife, Lucille. The Hoovers made several trips to Gunayala and became deeply concerned with preserving fine Guna textiles, which deteriorate in the tropical climate. In 2010 came a smaller donation of two complete molas and two rare sets of politically themed panels from Dr. Jeanne Marie Stumpf, an anthropologist at Kent State University who briefly visited Gunayala in 1986. These objects represent the work of a later generation of mola artists.

The exhibition features generous loans from Denison University, which holds one of the largest and most important Guna collections in the United States. The majority were donated in 1972 by Dr. Clyde Keeler, a Denison alumnus and geneticist whose research repeatedly took him to Guna territory. One Keeler mola depicting a lunar eclipse brings together his research on albinism, which is common among the Guna, with his interest in Guna culture: according to Guna lore, an eclipse occurs when a sky dragon attempts to eat the moon, and this can only be stopped when an albino, a Child of the Moon, shoots the dragon with an arrow.

This history of the mola is inseparable from the Guna’s struggle for independence. In 1918 Panamanian president Belisario Porras began taking steps to forcibly suppress Guna cultural practices, including their unique style of women’s dress. Guna people met this attack on their ethnicity with fierce resistance, and making and wearing molas became an act of political protest. In 1925 the Guna won the freedom to maintain their ethnicity and govern their own affairs, eventually gaining complete autonomy over their territory in 1938.

In the years following the Guna Revolution, the mola has transcended its role as a garment to serve as a visual embodiment of the strength and survival of Guna identity. At the same time, molas remain practical elements of daily life as clothing and personal expressions of individuality, and are thus subject to changing fashion trends from one generation to the next. A look at how molas evolved over the past century demonstrates the way in which their design is a blend of tradition and innovation.

Guna women began making molas around the turn of the 20th century, when they were already well engaged in foreign trade networks that provided access to cloth, thread, and needles. From these imported goods, they invented a new style of traditional dress that reimagined the geometric patterns once painted on the body. To produce these designs within fabric, Guna women developed the use of reverse appliqué, a technique that involves layering fabrics of different colors, cutting slits in the upper layer or layers, and folding back the cut edges to expose the color beneath. Additional details are added with appliqué, in which pieces of fabric are sewn on top. Early molas typically have highly abstract designs executed in a color palette restricted primarily to red, orange, and navy. These garments, called “grandmother” molas, are larger in size and drape loosely on the body.

In the mid-1900s, molas became progressively smaller and more formfitting, with cap sleeves in bright colors. The panels themselves became more colorful as artists started inserting patches of different colored fabric between the top and bottom layers to increase the range of colors revealed through reverse appliqué. Various stylistic and thematic trends fell in and out of fashion from one decade to the next. For instance, black-and-white molas trended in the 1960s and 1970s, and biblical subjects were especially popular in the 1960s.

By the 1980s, access to more types of fabrics led to innovations in sleeve styles. Cotton remained the favored fabric for the panels, but synthetic fabrics were used to construct the rest of the blouse, and the sleeves became more voluminous. Today, Guna women make molas with an assortment of necklines and sleeve styles, with a preference for sheer, billowing fabric.

Through changing trends, molas remain a powerful symbol of tradition. Artists assert that the image on a mola panel is less important than the mola itself as a carrier of cultural meaning. Fashioning Identity explores the mola as both a cultural marker and the product of an artistic tradition, demonstrating the powerful role women artists play in the construction of social identity. A booklet accompanying the exhibition can be found on the museum’s website.

Cleveland Art, Fall 2020